Healing Extremism

How does a white supremacist go from hate to healing, from extreme division to unity?

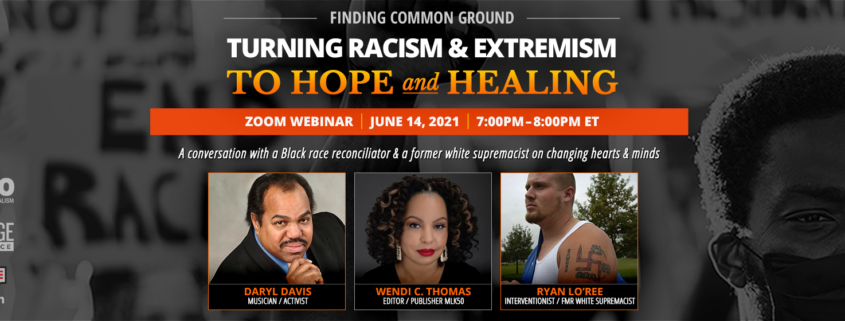

This was the subject of Common Ground Committee’s most recent webinar, “Turning Racism & Extremism to Hope and Healing,” on June 14, featuring Daryl Davis, a musician and race reconciliator, and Ryan Lo’Ree, an interventionist and former supremacist.

The webinar was a kickoff to the National Week of Conversation, a series of discussions aimed to shed light on what individuals can do to help heal divisions in our society. Below are some excerpted highlights of the event, moderated by Wendi C. Thomas, founding editor and publisher of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, an award-winning, nonprofit newsroom focused on poverty, power, and public policy.

WT: We’re joined by two extraordinary human beings tonight who have devoted much of their lives to confronting racism and extremism head-on to help bring harmony and healing to our society. Daryl is an accomplished boogie-woogie and blues piano player who has shared the stage with legends such as Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and B.B. King. He’s also spent over 35 years using the power of human connection to convince over 200 people to leave white supremacist groups and renounce racism. Daryl’s work has even taken him to KKK rallies—this is a brave man—complete with chanting and burning crosses. And because of his efforts, over two dozen Klansmen have actually given him their robes, and some have even become close friends. Daryl was even invited by the KKK’s Imperial Wizard of Maryland to be the godfather of his daughter. Now let me introduce Ryan Lo’Ree. Ryan is a former white supremacist who turned away from hate. He grew up in the very poor community of Flint, Michigan, where many children end up in gangs or prisons. And both of those actually happened to Ryan. He came home after serving in the military, found himself broke and was drawn into a group called the Rollingwood Skins. After counseling and self-education, he is now with Light Upon Light as an interventionist. He’s working to deradicalize others who have been lured into extremism and white supremacy.

WT: Daryl, let’s start with you. You’ve convinced hundreds of white supremacists to renounce racism over the course of decades. Are you surprised that these groups are on the rise? And how do you think we got to this point?

DD: Okay, well no, I’m not surprised. Yes, they’re on the rise, but they’re not on the rise as most people would perceive it. Because they’ve always been here. In recent years they’ve come out from under the carpet, out from the closet. You know, they– they’ve felt emboldened. What you’re looking at is two decades from now, in 2042, two decades, this country’s population will, for the first time in our history, become 50/50 — 50% white, 50% non-white. And while there is a large segment of the white population of this country that welcomes that, there is a certain segment that is becoming unhinged about it. They feel that their identity is being erased. They call it the browning of America, or white genocide through miscegenation. When I first started this kind of work about 37 years ago, there were the Ku Klux Klans and neo-Nazi groups and some white power skinheads. Now you got those same three, plus the Proud Boys, the Boogaloo Boys, the Oath Keepers, the Three Percenters, on and on and on, the alt-right. You have all these groups saying, “Come join us. We’re gonna take our country back.”

WT: Ryan, I want to turn to you. To help us understand what’s going on in this country, can you explain how you became a part of a hate group?

RL: Yeah, I was in a very tough economic position in my life at the time. I was just getting out of the military. It was hard to find a job living in the city of Flint. My family– going generations back have always been General Motors workers and many of my friends. And so, when General Motors struggles, so do they. So, I was in a very tough economic situation. I had an uncle who just got out of prison. He was actually part of a hate group while he was inside. He came to me, knowing that I was hurting at the time, like many hate groups do– to vulnerable people, and said he had some people he wanted to introduce me to. And because I had just got out of the military, I believe that I was still looking for that, like, that brotherhood. And you know, they lured me right in. Did I believe all the philosophy right away? No. But I think a lot of what they were playing on was my anger, my anger with the U.S. government– my anger with the fact that you know, I was a veteran and couldn’t get a job.

WT: How did you get out? How did you manage to extricate yourself?

RL: So, with me, is that I was incarcerated. And through that incarceration, I was able to separate myself from the group. I had other people that had come to me, friends of mine from before I’d ever joined these groups, that said, “Hey, I still love you, I still care about you. “I know that you made these mistakes. I know that this isn’t you.” And that was very, very important for my transition and for my transformation. It’s very important for us, too, when we do our interventions to be the same way. Daryl has said this many times, you can be empathetic without being sympathetic with the person. And having that empathy just allows them to actually sit down at the table with you so you can start a conversation, to even begin to understand whether or not you can deradicalize this person or not. Because not every case is a success story.

In mine, though, it was. I had the support of my family. I had a support system of friends that were still there for me. And I had an inmate at the time that actually was very understanding of my past. We grew up in the same city. And he turned me on to some different civil rights leaders that he had read books about, one of them being Dr. Cornell West. So, there was education. But there’s a lot of psychology that comes into it, and it doesn’t just happen overnight. It’s definitely a long process. And it’s a process that’s really underfunded in this country to help with intervention work.

DD: When I was a kid there was the saying, “a tiger does not change its stripes.” “A leopard does not change its spots.” So, when I first got involved in this, you know, I just thought, “A Klansman, is not going to change his robe and hood. That’s who he is. That’s who she is.”

But I learned something. What can be learned can become unlearned. And yes, a tiger and leopard do not change their stripes and spots. But that’s because they were born with those stripes and spots. A Klansman is not born with his robe and hood. It is a learned behavior. And what can be learned can become unlearned. But we must put in the time. A missed opportunity to dialogue is a missed opportunity for conflict resolution.

WT: Ryan, talk to me a little bit about the work that you and Daryl have done together.

RL: There are different tactics and ways that you can intervene, and different types of situations. Sometimes it’s helping somebody to get over someone who passed away, and who they found out had something like this go on in their life. Or a family member whose son joined a hate group and they want to know what can they do to help pull them out.

DD: We give them support. Because coming out of these types of groups, there is a stigma attached. And even after an extremist quits the group and pays their debt to society or whatever, it’s still hard to shake. So, when these people truly give it up, here’s the irony,

they get very little support from those who wanted them out in the first place — because they’re always leery and suspicious. “Oh, you know, I don’t know if I can trust him.”

Well, when they don’t find that support, then where do they go? They can’t go back to the group they just left, because they’ve betrayed that family. But they’ll find some other group that will accept them. And so, this is why it’s really important for people to provide that support so that they can stand on their feet, work their way through the criticism, and have people accept them back into society again.

WT: Let’s talk about George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter Movement. One thing that stood out about these demonstrations is there were a lot more white people participating than there ever had been. Daryl, is that a positive sign to you?

DD: Absolutely, absolutely it is. At the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, when the power structure looked at those protests and marches, they saw an ocean of Black people with a few white people mixed in. Now fast forward to 2020 in the wake of the George Floyd lynching. What did the power structure see? They saw an ocean of Black people, and an ocean of white people, marching together for the same cause. We had never seen that before. The ripple effect is happening. Places like NASCAR banning the Confederate battle flag. Food brands like Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben’s changing their labels. Legislation being passed to remove Confederate statues, to change the names of buildings named after slave owners. We’ve never seen things happen that fast [snaps fingers].

WT: Ryan, in white supremacist and extremist groups, what were the reactions that you heard to the Black Lives Matter rallies last summer?

RL: With movements like BLM, you’re always gonna have another movement on the hate side that tries to counter that. Like Daryl had said earlier, hate groups have always been here. But there was an uptick in different types of hate groups that started to come out. With BLM I’ve only seen very peaceful marches, never anything violent. But there are certain factions that aren’t peaceful, and it only takes one sour apple. It gave a lot of these white power groups a way of trying to recruit. “Look, they’re destroying their communities, they destroy your communities. They don’t care.”

WT: Has it become harder to extract people from hate groups since George Floyd was killed?

RL: Yes, honestly, it has. I don’t want to say cancel culture is the reason why, but closing down the extremists’ sites and banning groups from Facebook but, when we cut off anybody’s voice in this country, there’s a reaction. When we start to take away their ways of speaking to each other, you’ve basically created the lone wolf terrorist, the domestic terrorist.

WT: Ryan, because of the work you do, did you– did you ever anticipate something like the January 6th insurrection happening?

RL: Oh, I saw it happening. Ten, 20 years ago, even when I was part of the group, this is something that was talked about. They had talked about the race war of 2020 for years—before we ever started looking at 2040 as a date.

DD: And as we are approaching that date, that 50/50 point, we’re gonna see more and more of these lone wolves. Take our country back, make America great again, all that kind of stuff. People join these groups. But then when the group fails to take it back or whatever, they say, “You know what? The Klan can’t do it or the neo-Nazis can’t do it. I’ll do it myself.” And that’s when someone like Dylann Roof walks into a Black church, and boom, boom, boom. Or Robert Bowers goes into the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh and murders 11 Jews. And this is why it’s so important to address this issue now. You know, they’re looking for what’s called RaHoWa. RaHoWa, R-A-H-O-W-A, it stands for racial holy war, or for short, the race war.

Every time they raid one of these lone wolves’ home or property, what do they find? They find a cache of automatic weapons that they’re stockpiling for RaHoWa.

WT: I want to pivot and talk about solutions, takeaways for the audience. Both of you have emphasized the importance of listening and discussion. Give us some things we can do, how you convince others to turn away from hate. What is it going to take to end the notion of white supremacy?

RL: It’s empathy. I don’t necessarily have to be sympathetic with what somebody is doing to be able to sit down at the table with them. But if I can show them empathy and saying that look, “I understand that you’ve made some mistakes. I understand that you’ve learned what you’ve learned here. But I think that maybe you’ve been taught the wrong way.” You don’t start the conversation about race and hate and anger. You start the conversation on some things that maybe we have in common, or what may be one of my Black friends has in common with them. Then they see that person, and have to think, what is it I’m hating? It’s all about educating that person to get them away from that ignorance. But the intervention comes in many different ways. We have a hotline that’s set up that people can call into, and some people are okay with talking to you on the phone. Some people didn’t want any type of conversation at all, and it takes a year or two of just discussing stuff with them on the internet or through email before you’re able to actually get this type of conversation.

WT: Daryl, how do you change the mind of a racist? I know you have a really specific process.

DD: As a child, I traveled a lot because my parents were U.S. Foreign Service. So, I lived in different countries during the formative years of my life. And now as an adult musician, I tour all over the world. And all, that is to say, is that I’ve been exposed to a multitude of ethnicities, colors of skin, religions, persuasions, ideologies, beliefs, et cetera. And all of that has helped shape me. And what I’ve realized is this: that no matter how far I go from this country, whether it’s next-door to Canada or to Mexico, or halfway around the planet, and no matter how different the people maybe who I encounter, I always end up concluding that we all are human beings. And as such, we all want these basic five core values in our lives. We all want to be loved. We all want to be respected. We all want to be heard. We want to be treated fairly. And we want the same things for our family as anybody else wants for their family. If you employ those five values, when you find yourself in a society or a culture in which you are unfamiliar, people are willing to sit down and talk with you, and there is a chance to plant that seed.

RL: Be empathetic enough to listen to them and try to get an understanding of why they got to that point in their life in the first place. We’re all human beings. We all make mistakes. But we all can be redeemed.

Check out the Let’s Find Common Ground Podcast for more information on finding common solutions to today’s vital issues.