The point of striving for common ground is not to force an agreement on issues — it’s to foster conversations that lead to better understanding.

As we journey into a new decade, it’s natural to consider where we stand as a nation and as a people. To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, are we better off today than we were 10 years ago?

The only certainty is the uncertainty we face. The president of the United States has been impeached, a critical election cycle looms, and our nation appears more polarized than it was at the start of the last decade.

It’s not all doom and gloom. A survey released in December by Public Agenda/USA TODAY/Ipsos found that almost 40% of Republicans and nearly 50% of Democrats would cross party lines to elect a leader who can bring us together.

This isn’t exactly comforting to those on the political extremes, who tend to view bipartisan cooperation as working with the enemy and finding common ground as a capitulation of principles. As co-founders of the Common Ground Committee, a nonprofit dedicated to bringing light, not heat, to public discourse, it’s a criticism that’s all too familiar. But it’s one that deeply misunderstands the meaning of the word. The value of common ground is not just the outcome. It’s the conversation.

Conversations about politics should be productive and healthy. Instead, it’s increasingly viewed as a pointless and destructive exercise. Almost 40% of Americans say politics has them “stressed,” while 1 in 5 reported that a friendship had been “damaged” as a result of a political argument, according to a University of Nebraska-Lincoln study.

This matches what we hear from folks all over the country: When given the choice to talk about politics with someone who holds different views, their instinct is to avoid conversation. After all, why risk a friendship when there isn’t likely to be a consensus?

Not all conversations will end in agreement, which is fine. Inevitably, there will be areas where there is no common ground to be found. Even so, the point of searching for common ground is not to force-feed agreement on a particular issue — it’s to foster a conversation that ultimately leads to greater understanding.

‘Ignorance breeds fear’

That was the attitude of African American blues musician Daryl Davis when he decided to engage in dialogue with members of the Ku Klux Klan. “Ignorance breeds fear,” Davis said, and his mission was to show these avowed racists that he was no different than them. Ultimately, he befriended 20 KKK members and even became godfather to one of their daughters.

The lesson here is not that we should brush aside hateful acts in the name of civility. It’s that we are all human beings, and we do ourselves a disservice when we stop talking to each other, even with those we consider hateful. Davis’ actions did not provide support or solidarity to the racist views held by these individuals. What his actions did prove is that even the most extreme in our society can change if we are willing to listen and engage.

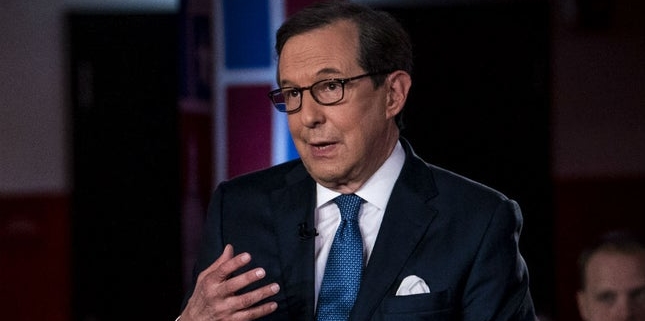

To be sure, this is not easy, especially when most examples of dialogue in national media devolve into shouting matches. That’s why there’s a growing movement with the goal of showing Americans what good conversation looks like. Common Ground Committee is one such group, but organizations like Living Room Conversations and Better Angels also are bringing opposite sides together for conversations. At one Living Room Conversation we participated in, by the end, the group agreed that climate change had to be addressed but that it needed to be done in a way that considered the economic impact on everyday citizens.

Listening can lead to learning

Last fall, we released the 10 attributes of what we call Common Grounders. One of those attributes is to listen and learn from others’ personal experiences. This is the essence of the commonground movement.

When we brought retired Army Gen. David Petraeus and former Ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice on stage for a recent event, the audience was inspired by just how much they found agreement and how both made a point to listen to each other before responding. In an era of shouting and sound bites, it was a refreshing change of pace.

We live in a world full of ideas. The reality is we’re not going to agree on everything. Nor should we. But disagreement should not be a barrier to conversation, to learning, to understanding. If we make the decision to avoid difficult conversations, we’ll never be able to make progress on the issues that matter to all of us. We may start this decade deeply divided, but if we commit ourselves to engaging in dialogue, there’s no reason we can’t end it united.