The Middle Shelf: Part 3 – A CGC Guide to Finding Common Ground through Reading

One of the seminal books that should be required reading for anyone seeking to understand polarization and how there could be a possibility of bridging divides and reaching common ground is The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt. While the book has been out since 2013 we still want to recommend it because we find the author’s empirical approach to polarization based on his work as a social psychologist to be a rational way to view politics during this rather confusing time.

Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist at the NYU-Stern School of Business. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1992, and spent most of his career (1995-2011) at the University of Virginia.

Haidt’s research examines the intuitive foundations of morality, and how morality varies across cultures––including the cultures of American progressive, conservatives, and libertarians. He was named a “top 100 global thinker” in 2012 by Foreign Policy magazine, and one of the 65 “World Thinkers of 2013” by Prospect magazine.

Haidt considers himself a centrist politically. A couple of years after he wrote the book, he explained that his main goals in writing The Righteous Mind was to “examine through applied psychology how moral psychology can help us understand the forces making American democracy so dysfunctional? Also how can moral psychology help citizens understand each other across the political divide?”

What he found was that all political movements have blind spots even among those that acknowledge moral truths. The three pillars of political thought being the left right and libertarian, according to Haidt, all have their truths about how to create a society that is humane. The problem is that ideology, even if well meaning, can distort and make us blind to how others think.

Few books on this type of subject begin with the origin of life starting with bacteria! By looking at morality through both cultural and biological lenses, we can get unique insight into how humans make judgments. It is a multi-genre study that takes the reader across the academic fields of study ranging from social and political sciences as well as the humanities.

In his introduction, Haidt notes that there are aspects of the topic that are not easy:

“Etiquette books tell us not to discuss [politics and religion] in polite company, but I say go ahead. Politics and religion are both expressions of our underlying moral psychology, and an understanding of that psychology can help to bring people together. My goal in this book is to drain some of the heat, anger, and divisiveness out of these topics and replace them with a mixture of awe, wonder, and curiosity.”

The book is divided into three parts or principles:

- Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second

- There’s more to morality than harm and fairness

- Morality binds and blinds.

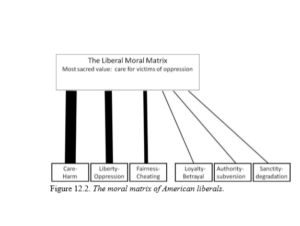

Throughout the book Haidt offers graphics to illustrate his points. One of the ones we found particularly enlightening was:

There is so much more about this book that makes it an excellent addition to your summer, or any season, reading list. For more on this book please visit Jonathan Haidt website.

As always, we would like to hear from you about your summer reading plans. Are there new books or any classics you think are worth reading on the road to common ground? Let us know what you think of our first two choices.