In 1986, a Black blues artist and a white Ivy League graduate made history. Today, their music lives on through a new generation – and has sparked a new call for hope & unity.

This spring, in the midst of the unfolding coronavirus crisis and national protests over police brutality and racial inequity, Common Ground Committee co-founder Bruce Bond opened his inbox to a message from his old college roommate, Adam Gussow.

Gussow, a well-known musician on the blues scene, had just gotten out of the studio after recording a new album by Sir Rod & The Blues Doctors. Its title song, “Come Together,” spoke to the mission of healing polarization in America. His offer: would Common Ground Committee like to use the music as an inspirational message to followers?

Gussow, a well-known musician on the blues scene, had just gotten out of the studio after recording a new album by Sir Rod & The Blues Doctors. Its title song, “Come Together,” spoke to the mission of healing polarization in America. His offer: would Common Ground Committee like to use the music as an inspirational message to followers?

The answer, of course, would turn out to be yes. As a musician himself, Bond recognized the power of music to touch people’s souls. And as a friend watching Gussow’s life-changing odyssey through the blues, he had seen firsthand that it can be a truly transformational force.

Satan & Adam: an unlikely pair becomes a force in the blues world

When Bond and Gussow first met as students at Princeton University in the late 1970s, Bond couldn’t have predicted that Gussow would become an internationally recognized blues harmonica player.

“I had him pegged as a professor,” says Bond, recalling that Gussow was into literature. “He was always a very good thinker, and a very good writer.”

Bond and Gussow did, however, share an interest in playing the guitar. Eventually, they joined a pair of other students to rent an off-campus apartment; a maverick move, in those days. Although he had played blues harmonica back in high school, Gussow had gained a reputation as a funk guitar player for Spiral, a band Bond calls “the best jazz band on campus.”

It was later, in 1986, that a chance meeting changed the trajectory of Gussow’s life. By then, having dropped out of grad school at Columbia, Gussow was tutoring at Hostos Community College in the South Bronx. He had also started playing the harmonica again in the aftermath of a bad breakup. Gussow was wandering the city with his harp in his pocket when, busking on a Harlem sidewalk, he saw an older musician at work whose voice was reminiscent of the raw power of Muddy Waters, and his mastery of the guitar effortless.

In a city then brewing with racial tension, on a block just down from the Apollo Theatre, there were no white faces to be seen. But Gussow had to stop and listen to “Mr. Satan.” After a bit, he pulled his harmonica out of his pocket and asked if he could play along.

After Gussow’s promise that he wouldn’t embarrass him, Satan agreed. Soon, they found a natural groove together. Gussow asked if he could come back again the next day – and kept coming back.

![Satan and Adam [Corey Pearson]](https://commongroundcommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Satan-and-AdamCorey-Pearson.jpg)

Satan and Adam: Adam Gussow with Sterling Magee on the streets of Harlem in the 1980s

It took some time to discover who Mr. Satan really was: a virtuoso of the 1960s music scene, Sterling Magee. Originally from Mississippi, Magee was a natural guitar prodigy who had recorded with Marvin Gaye, Etta James and more, as well as writing songs.

Despite his talent, Magee had failed to reach stardom himself. Suppression by record labels and unfair compensation for Black artists convinced him to leave the industry; and, by the 1980s, he had reinvented himself as a one-man band and street prophet, playing on the Harlem streets for “his people.”

Enthralled by Magee’s hard, deep blues, Gussow committed himself to the duo. For his part, Magee recognized the harmonica and the unlikely pairing of the two musicians on the streets of Harlem made the act a greater success. Inevitably, a white Jewish Ivy League student & black Misississippi blues man playing music in the streets began to attract attention. Documentary makers began filming footage of their story. Perhaps their biggest break came in 1987 when the Irish band U2 saw them playing in the streets and included a 30-second clip of Magee’s song “Freedom for My People” on their Rattle & Hum album.

By 1990, with the release of their first demo cassette, they officially became Satan & Adam, a musical duo who would help shape the New York blues renaissance of the 1990s. It was the beginning of what felt like a meteoric rise. Satan & Adam started getting bigger bookings for bigger crowds. They recorded several albums and began touring internationally.

That came to a halt in 1998 when Magee, who had moved South with his wife, disappeared. It would take years for filmmakers to track him down again. After suffering a nervous breakdown, and eventually a stroke, Magee had lost his ability to play guitar and had entered a nursing home.

For Gussow, who still recalled the master musician who was his blues apprentice and idol, his first visit to Magee in the nursing home was both shocking and saddening. Yet that was not to be the end of the music.

Satan and Adam: Sterling Magee and Adam Gussow on a festival stage, 2012

A staff member at Magee’s nursing home, after discovering Magee’s story on the internet, invited a local blues musician to come in and play. Immediately, the music brought Magee to life. After a few visits, he took the guitar off his wall and began strumming along – and with every session, he was restored.

Before long, Gussow and Magee reunited and the unlikely duo was playing gigs again. From local bars to the New Orleans Jazz Festival, Satan & Adam played a second verse in their act, recording several albums and touring.

Their remarkable journey has been captured by Gussow, who, as a Professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi, has written several books about the history of the blues and their story as “blues survivors.”

And, after decades in the making, filmmakers released the documentary Satan & Adam through Netflix in 2019. Gussow often hears from people that the film made them cry, and he has his own theory on what brings the tears.

“The concept of ‘beloved community’ was a civil rights dream in the era of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” says Gussow. “For a variety of reasons, that dream went away. But I think seeing the story of us making music together reminds people what’s possible.”

A new generation reprises the music

This remarkable second act was, once again, not the end of the story. In the summer of 2019, Magee’s nephew Rod Patterson watched the documentary Satan & Adam and realized both he and Gussow had learned the blues from Magee.

Patterson’s mother, Ollie Mae, was Magee’s sister. Before moving to Harlem and pairing up with Gussow, Magee had spent some time living with the family. As a young boy, Patterson’s first exposure to live music was watching his uncle play guitar and sing in Ollie Mae’s living room.

“He would jam in the living room, and it made a big impression on me,” recalls Patterson. “I remember him smiling while performing.”

Patterson himself has experimented with many art forms over the years. As a teen, inspired by Michael Jackson, he fell in love with dance and beat hundreds of other performers at his first dance competition at age 15. As an adult, he built on his love of dance and music to engage students with an anti-bullying message he brought into Atlanta schools, preventing several teens from committing suicide. And as a graphic designer, he worked on the music scene and began to explore photography.

For most of his life, however, Patterson’s most intense vocal performances had been reserved for karaoke Motown tunes after a long day of work – truth be told, he says with a laugh, a habit not strongly encouraged by his wife.

That changed one day when Patterson was taking photos at a nursing home full of Black residents, where a performer was singing John Denver songs to polite acclaim. Patterson, invited to take his turn at the mic, pulled up a Sam Cooke karaoke number on his phone. Suddenly, the audience came to life.

“It went from a sleepy affair to a full-fledged celebration,” he remembers.

When doctors and nurses started coming out to listen to the number, both Patterson and the management realized his vocal performances had real star appeal. Administrators asked him to come back, and began sending him out to sing at other nursing homes.

Along the way, Patterson saw for himself how powerful music can be as a healing force. Once, after singing to a woman with dementia and touching her hand, her aide excitedly reported that for the first time in years the woman was responsive.

“Miss Agnes came back!” she told Patterson.

It was a few years later that Patterson, singing along to some recordings of his uncle’s music, found his voice twinning with Magee’s.

“That was the first time I thought, ‘I think I could sing his stuff,’” Patterson recalls.

Moving to the blues began to seem like the next step. In November 2019, after seeing the Satan & Adam documentary, Patterson emailed Gussow to explore performing some of Magee’s music together.

“It’s a shame that his music has to stop,” says Patterson. “I don’t want to take over the music, but I do want to pay tribute to it.”

Sir Rod & The Blues Doctors: (left to right) Adam Gussow, Rod Patterson & Alan Gross

Together, Gussow and Patterson devised a plan for Patterson to travel to Oxford, Mississippi in February 2020 and record a demo album of Satan & Adam tunes with Gussow’s current band, The Blues Doctors.

Knowing it’s not always easy for a new artist to jump in with band musicians, Gussow wasn’t sure the sessions would be a success. But Patterson fit right in – in more ways than one. On a personal level, Gussow and Patterson shared similar recollections of Magee’s habits and philosophy on the blues.

“As we started talking, we realized we often had the same story,” recalls Gussow.

Musically, too, things quickly fell into place. On his first day in the studio, Patterson recorded six to eight songs with The Blues Doctors.

“It was uncanny – familiar and strange at the same time,” says Gussow. “We knew an act had been born.”

A rallying call for hope and humanity

While the plan was to stick to material from the Satan & Adam songbook, at the eleventh hour, a new song was born that both Patterson and Gussow immediately saw held special power.

In 2017, in a band “woodshed session,” The Blues Doctors recorded an instrumental track called “Yes We Do.” A euphoric blues rock song that strayed into jam band territory, Gussow realized the music was striking a chord with The Blues Doctor’s YouTube following.

At 4 PM the day before he was scheduled to drive to Mississippi for the final recording session, Patterson opened his email to find a message from Gussow inviting him to check out the tune and possibly write some lyrics. With so little time left in the studio, Patterson’s first reaction was to hope he wouldn’t like the music.

That was not to be.

“The second I clicked on it, I fell in love,” Patterson recalls. “It spoke to my soul.”

Inspired by the hippie vibe of Janis Joplin’s “Piece of My Heart,” he poured out a set of lyrics with a rousing call to overcome difference, see the humanity in others and unite to make positive change.

“I love people, and I hate division,” says Patterson, of the song. “We need to come together. We have bigger fish to fry than this black & white thing.”

Written in mid-February, Patterson’s lyrics were penned at a time when COVID-19 was not yet an American crisis and the killing of George Floyd, on the heels of other incidents of racial violence, had not yet sparked nationwide demonstrations and friction. Just a few weeks later, the music would seem even more prescient.

“It’s prophetic,” says Gussow. “It speaks to where we are today, with this pandemic and also the virus of racism.”

Knowing Bond to be a fellow musician, and appreciating the work Common Ground Committee is doing to overcome division and move toward progress, it was a natural inspiration for Gussow to reach out with an offer to share the song and its message of hope.

“We so much need organizations like Common Ground Committee that speak to the liberal center,” says Gussow. “We need to do something to heal the polarization in this country. Like the song says, ‘You wear red, I wear blue. We’ve got to heal our vision.’”

For his part, Bond recognizes in Gussow the essence of what it means to be a Common Grounder.

“He is constantly checking the way he thinks about things, and seeking to understand rather than demonize,” says Bond.

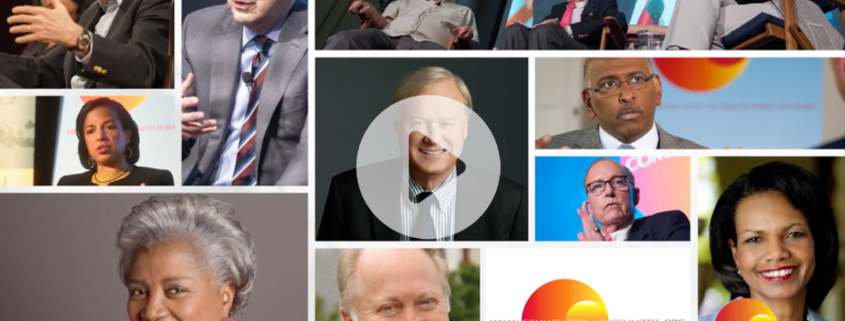

In the words of “Come Together,” Bond hears a message that is spot on. It was a natural fit to put together a video that marries the song’s stirring music and lyrics with imagery of Common Ground Committee guests – including some of today’s luminaries in the world of politics, foreign policy and more – finding agreement on some of today’s most divisive issues.

“Coming together is what we need to do in this country, and the lyrics are exactly what we preach,” Bond says.” Open your eyes, and open your heart. It takes real humility, a willingness to be vulnerable and to listen to what others have to say.”

Watch: Adam Gussow and Rod Patterson talk with Common Ground Committee about the making of “Come Together” and how we can all play a role in healing conflict.

At a time when people are missing the connection of live performances and surrounded by division among neighbors, Bond hopes the song will leave listeners with a renewed sense of joy and possibility.

“The world is in need of hope, and there’s reason to have hope,” says Bond. “At our forums, we are seeing people put aside their differences and work together. So we hope the spirit of this song and video will remind people what’s possible. You know, when you see Condi Rice and John Kerry laughing together and agreeing on things, it makes you stop and think.”

For Gussow and Patterson, amongst the joy of renewing the magic of Satan & Adam and creating new art that speaks to what the nation needs, there is a bittersweet note.

Magee, now 84 years old, hasn’t yet heard “Come Together.” Last week, he was admitted to intensive care with a diagnosis of coronavirus. While he can’t receive visitors, they are hoping a kind nurse and the power of technology will let him hear the album and how his nephew is carrying on his legacy.

And with the power of music…who knows?

UPDATE: Since this story was written, Sterling Magee has recovered from coronavirus and has been discharged from the hospital. As Gussow says…you can’t kill Mr. Satan.

![Satan and Adam [Corey Pearson]](https://commongroundcommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Satan-and-AdamCorey-Pearson-640x321.jpg)

![Satan and Adam [Corey Pearson]](https://commongroundcommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Satan-and-AdamCorey-Pearson.jpg)